After the Storm

(Hirokazu Kore-eda, 2016)

After the Storm screens at the AMC River East 21 on Wednesday, October 19 at 8:15PM and Thursday, October 20 at 5:45PM. For additional ticketing information, refer to the Chicago International Film Festival website here.

There’s something to be said about giving up grand ambitions for living the most ordinary of lives, or so Hirokazu Kore-eda will have you believe. His films, all graceful, humanistic portraits of men, women, and children reconciling expectations with reality, display a cumulative wisdom that escapes most contemporary filmmakers’ worldviews. After the Storm, Kore-eda’s latest, is his most accomplished work yet, possessing the sort of weary-eyed clarity into the fears and anxieties that plague dreamers who have failed to blossom from the promise of their youth.

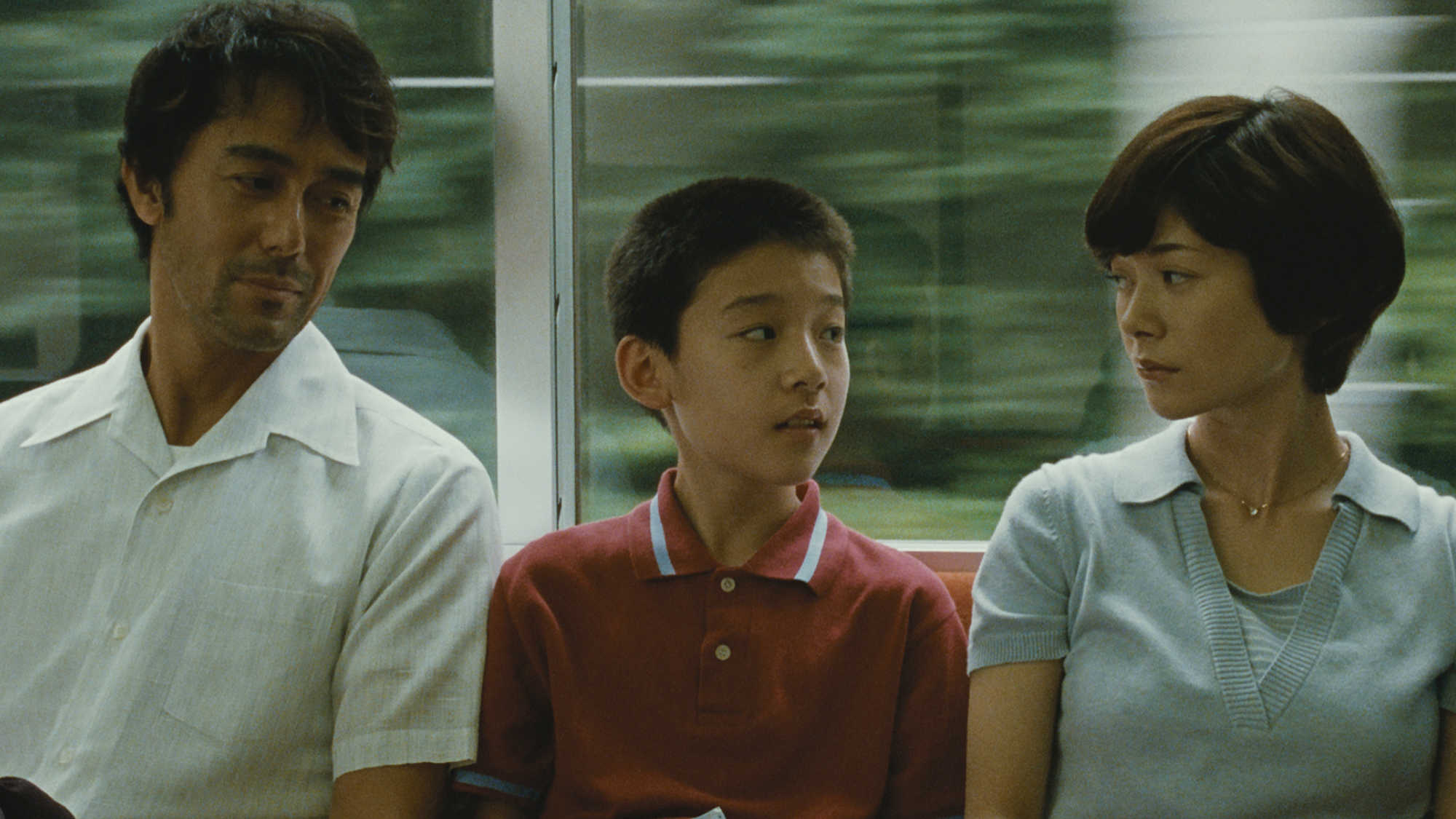

The film pivots on Ryota (Hiroshi Abe), a once successful novelist in his youth who now works as a private detective. He tells his friends and family that the profession is just fodder for his next novel, but it’s the kind of line that grows less convincing every time he says it. The details of Ryota’s errs in judgment accumulate as he visits his mother, Yoshiko (Kirin Kiki) – she finds her son roaming her apartment and bluntly asks if he visits for money. His fecklessness with money – exacerbated by his gambling addiction – has spurred much of his marital problems, as he perpetually fails to make child-support payments to his ex-wife Kyoko (Yōko Maki) for their son Shingo (Taiyô Yoshizawa).

On the periphery of the frame is the threat of an encroaching typhoon, which isolates the four primary characters under the same roof for the film’s final act. Beforehand, however, Kore-eda playfully observes each character individually, zoning in on their specific qualities that may be passed down onto Shingo. And that’s the passing suggestion that Kore-eda makes with After the Storm, which is concerned with the legacies that transfer from one generation to the next. For example, Ryota’s problems with money were inherited from his deceased father, with Kyoko concerned when Shingo is caught with lottery tickets. Some legacies and habits prove to be inescapable, laced into one’s DNA from birth, where past becomes present. Kore-eda observes these repetitions in human behavior, forcing not just Ryota, but also Kyoko and Yoshiko, to confront their immediate consequences.

Kore-eda’s patience lends to some surprising moments on the passages and pilgrimage of aging, as well as the inherit falsehoods associated with the wisdom of elders – it’s Shingo who seems most confident with his abilities and limits as a child. The elders that orbit around him are in disarray, where their failures have generated self-doubt and pressures that cloud their judgment. But as with Kore-eda’s previous work, he reserves the right to judge these characters, instead allowing them to figure things out for themselves. As Yoshiko discusses with Ryota later in the film, she hopes to find her way in the present, leaving behind the petty failing of the past. And before she forgets that, she tells Ryota to write that down – if it’s not a philosophy to live by, then maybe it’ll make good fodder for a novel.